Chapalichthys pardalis (including peraticus)

Álvarez del Villar, J. (1963): Ictiologia Michoacána. 3. Los Peces de San Juanico y de Tocumbo. Anales de la Escuela Nacional de la Ciencias Biológicas 12 (1-4): pp 111-138

Collection-number: Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Cat. No. ENCB P543.

The Holotype is an adult female of 57.4mm standard length, collected by J. Álvarez del Villar in Tocumbo, September the 23rd, 1961. The Allotype, a male 62mm long and another 541(!) Paratopotypes of lengths between 13 and 63.5mm were caught with the Holotype. The Holotype of Chapalichthys peraticus, a female of 65.1mm standard length (ENCB P732) was collected by J. Barrera on May the 30th, 1963, the male Allotype (46.1mm SL) by the author on May the 23rd, 1962. About 180 Paratypes were collected at several occassions in the years 1962 and 1963, all from the Presa San Juanico.

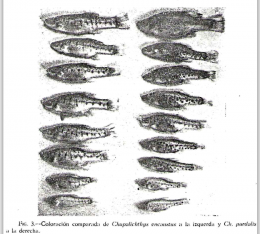

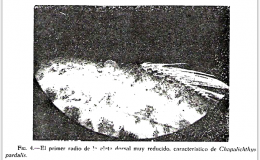

The left picture shows a comparison between Chapalichthys encaustus (left) and pardalis (right), the right picture a part of the dorsal fin of Chapalichthys pardalis from Tocumbo, focusing on the first reduced ray, the main characteristic following Álvarez del Villar to distinguish this species from peraticus:

The Holotype and all the other specimens used for the description were caught in the Manantial de Tocumbo, a spring fed pool, about 40km S of the Lago de Chapala in Michoacán. Again, the types used to describe Chapalichthys peraticus were collected in the Presa San Juanico in the vicinity of Cotija. This dam is about 20km N of Tocumbo.

The word "pardalis" is derived from the Latin word "pardus" with its origin in the ancient Greek language: There the word párdos (πάρδος) means "the mottled one" or "Panther", the adjective pardalis “mottled or coloured like a Panther”. Álvarez del Villar chose this epithet because he saw the colour pattern of this species disjunctive to others.

The generic name goes back to the year 1902 and Seth Eugene Meek. He didn't explain why he had chosen this name for Characodon encaustus, but most probably because of the type localition of this species, the Chapala lake. Chapala is for sure taken from the lakes name and the Greek word ἰχθύς (íchthús, íchthýs) means fish, so Chapalichthys can easily be translated with "Fish from the Chapala lake". The name of the Chapala lake itself is taken from the Nahuatl language and the lake is named to honor the last chief of the indigenous Aztec people, chief Chapalac, so in a more romantic way, you can say "the fish from chief Chapalacs lake".

Chapalichthys peraticus Álvarez del Villar (1963)

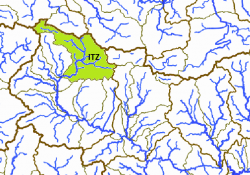

The Polkadot Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal state of Michoacán. It was described from the Ojo de Agua de Tocumbo in the town of Tocumbo, about 12km N of Los Reyes de Salgado and is also known from the Presa San Juanico about 20km NW of Tocumbo. Both habitats are connected via the Canal Lateral and merge into the Río Grande, that becomes the Río Itzícuaro after Los Reyes. This river is a western tributary fo the Río Balsas. In 2016, rumours came up (Domínguez-Domínguez, pers. comm.), that the bath in Tocumbo was emptied and cleaned with all occuring fish gone. After the bath has been filled again, a survey by Torres de León (2018) especially executed for an IUCN Redlist assessment supported this status and the species is possibly Extinct at the type location. Following the original description of pardalis and peraticus by Álvarez del Villar, both are barely distinguishable. As the habitats are separated by only 20km distance beeline and connected via a channel, no subpopulations are distinguished. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of the first 3 letters of the genus, followed by the first 2 letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

Actually, we distinguish two ESU's within this species, whereas the first abbreaviation, Chapa1 is taken for fish from the Manatial de Tocumbo. The second one, Chapa2 is in use for fish from the Presa de San Juanico.

The left map shows the Río Tepalcatepec basin from the Hydrographic Region Balsas on a Mexico map. The right map shows the Río Itzícuaro subbasin (ITZ), where the Polkadot Splitfin is restricted to its northernmost parts and historically known from only two localities:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Critically Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Critically Endangered/stable: „This species is known from only two areas in the upper Balsas River basin, the San Juanico Lake and the Tocumbo Springs, located ca. 25 km downstream along the outlet of the lake (Miller et al., 2005). For many years the San Juanico population was considered a separate species, C. peraticus (e.g., Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005), but recent genetic (Piller, unpublished data) and morphological analyses (Miller et al., 2005) indicate that there are insufficient differences between the two populations to warrant separate species status, although they do qualify for separate ESU designation based on morphology. Chapa1, from Tocumbo, is critically endangered and possibly extinct in the wild. Formerly it was known only from a small spring system that had been heavily modified as a swimming area. However, none have been observed there since 2015. Chapa2, from San Juanico, is also critically endangered, having a small population occupying the nearshore areas of the lake.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: no categoría de riesgo (no category of risk)

The Balneario de Tocumbo encompasses a clear spring and its outflow creek, now almost entirely modified into a concrete pool. The depths where the species could be found were not more than 1.0-2.0m, but they originally prefered about 0.5m. The natural substrates (now concrete) were silt, mud, gravel, rocks and boulders, concerning vegetation could be found green algae and sparse waterhyacinths in the outlet. Miller wrote about the spring temperatures varying from 21 to 24°C. In the Presa San Juanico, the fish live in pools and ponds with partially dense aquatic vegetation (mainly Ceratophyllum and Eichhornia), as well as dense reed on the shore. The substrates are mainly silt, mud, gravel and rocks. The water is clear to turbid. Radda measured a watertemperature of 24°C (February 1982) in a depth of 0.1m, but the temperature of the waterbody itself doesn't exceed 20°C.

This species has probably got a long reproductive period as 13mm long young fish were taken on September 23rd, 1963 by Álvarez del Villar and 18mm long ones on April 20th, 1979 by Kingston. She also mentioned two months before (February 17th) "all size classes". Individuals as small as 18 and 19mm were collected in late May and early January by Álvarez del Villar (1963) from the Presa San Juanico, suggesting a protracted breeding season.

The species was seen in the Balneario Tocumbo feeding from algae and aufwuchs and was attracted to insects fallen on the surface, so it might be herbivorous with adding animalistic food components occasionally. Bifid teeth and a long convoluted gut support the assumption, that the Polkadot Splitfin is predominantly herbivorous.

Silvery grey in both sexes with a yellowish-greenish glimmer. The fish show an irregular and close pattern of dark blotches, more prominent on the lower part of the body. The dorsal part shows smaller blotches or points, in males somewhat dusky superimposed. The blotches in the midline are forming an irregular lateral band. The fins are yellowish-grey in females and dark-grey in males. The caudal fin shows a bright yellow terminal band in males, delimited from the dusky part of the fin by a small dark line. Fins and opercle are non-spotted. The opercle is silvery coloured. Young specimens show few blotches evenly distributed over the sides.

At first appearance, males and females of the Polkadot Splitfin are not very easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Chapalichthys pardalis have a much bigger Dorsal fin than females. A difference in colouration is almost not visible, except for the usually much more intense yellow coloured terminal band in the Caudal fins of males and a yellow belly in females, but this second character is not always visible and changing with the individual. Females appear more slender than males.

In the original paper of Álvarez del Villar, the only species collected in the Balneario Tocumbo with the Polkadot Splitfin was the Poeciliid species Poeciliopsis infans, while Dolores Kingston (1979) mentioned additionally Neoophorus regalis. A survey of the habitat by a group from the Czech Republic (Slaboch et al.) in 2012 counted several species that were not found before, some of them exotics: The Goodeid species Goodea atripinnis and Ilyodon whitei, and the Poeciliid species Poeciliopsis infans, Poecilia mexicana, Poecilia reticulata and Xiphophorus hellerii. Still few individuals of Chapalichthys pardalis could be found. In 2017 Omar Domínguez Domínguez (pers. comm.) feared, that the population might be already extirpated due to cleaning processes of the pool. A survey of the bath by Oscar Torres de León (2018) revealed masses of the species already found by the Czech group, but no more Polkadot Splitfins. The reasons for the disappearance of this Goodeid species are not completely understood, but the numerous individuals from other Goodeid species that probably invaded the pool from the Presa San Juanico by a connecting channel (Goodea) and from the river where the outflow goes to (Ilyodon), the intensive cleaning processes and the modifying of the habitat into this concrete pool might have all contributed in this.

The species Chapalichthys peraticus, originally described by the same author in the same paper (Álvarez del Villar, 1963) from the Presa San Juanico, about 20km N of Tocumbo, was treated as a separate species by many scientists for about 50 years. Recent phylogenetic studies (Piller et al., 2021) revealed, that both previously described species are only one: Chapalichthys pardalis. Even when following the original description of pardalis and peraticus by Álvarez del Villar, both representatives of this genus are barely distinguishable.

Looking on the biotopes of Chapalichthys pardalis, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to none current, structured with rocks, roots and small areas with dense submerse vegetation. Intraspecific aggession is almost not observed, only sometimes between males of same size. Fry is rarely eaten, so it is possible to get fast a big and flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 150 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. A bit with roots and/or rocks structured tanks with few patches of dense submerse vegetation in the corners and bigger free areas to swim seem to do best with this species. The current should be none to moderate, especially as the oxygene level should be quite high (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, adults of this species feed mainly from algae and aufwuchs, so much light to help algae grow and feeding with vegetables and additionally fiber-rich middle sized food from animalistic sources will be best for this fish. In aquarium, it feeds very well from flake food, granulate and tablets, additionally freeze dried food like Brine Shrimps is eaten greedy. The species is anything else but shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially spring and river inhabiting species. Therefore an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species does very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 15°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 15°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Chapa1-ITZ-Toc

Population: Tocumbo (aka Balneario de Tocumbo, Ojo de Agua de Tocumbo, Manantial de Tocumbo, Tocumbo Bath)

Hydrographic region: Balsas

Basin: Río Tepalcatepec

Subbasin: Río Itzícuaro

Locality: Bath and effluent in Tocumbo

2. Chapa2-ITZ-PSJuan

Population: Presa de San Juanico (aka Chapalichthys peraticus)

Hydrographic region: Balsas

Basin: Río Tepalcatepec

Subbasin: Río Itzícuaro

Locality: E coast of the San Juanico dam (Presa de san Juanico)