Ataeniobius toweri

MEEK, S. E. (1904): The fresh-water fishes of Mexico north of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. Publication. Field Columbian Museum 93, Zoological Series 5: pp 138-139

Collection-number: Field Columbian Museum, Cat. No. FMNH-4519.

The Holotype is an adult female of 60.4mm standard length (2.38 inches), collected by W. L. Tower in August 1903.

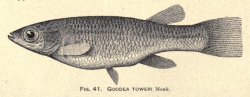

The left picture shows the first illustration of the Holotype of Ataeniobius toweri, the right one a picture of a ditch next to the Laguna Media Luna from 1974, a typical habitat of the Striped Splitfin:

Meek wrote in his description simply: Río Verde, San Luis Potosí. Unfortunately, there is a no more accurate type locality available.

The species is named after William Lawrence Tower from the University of Chicago who discovered the species.

The genus Altaeniobius was erected by Hubbs and Turner, published by Turner in 1937 and taken from the manuscript of the famous monography about Goodeids that Hubbs & Turner finally published together in 1939. The reason for the need of describing a new genus was that this species "lacks any trace of the trophotaeniae or nutritive rectal processes." The privative ἀ (á) at the beginning is followed by the Greek words ταινία (tainía or taenía) meaning band or ribbon, and βίος (bíos) meaning living. Combined the generic name can be translated with "living without a ribbon". This is a reference to the fact, that the fry has no trophotaenia.

Goodea toweri Meek, 1904

The Bluetail Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal state of San Luis Potosí and part of the Río Verde fish fauna. It inhabits several thermal springs and outlets S of the town of Río Verde, draining into the Arroyo Santa Rita (like the Lago Manantial de la Media Luna), a tributary of the Río Las Calabazas that lateron merges into the Río Verde, and several springs and outlets N of the town of Río Verde, draining into the Río Choy and the Canal Acequia Gigantal, both affluents of the Río Verde as well. Few springs S of Río Verde drain directly into the river of the same name (e.g. Charco Azul). No subpopulations are distinguished. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

No differences strong enough occur in Ataeniobius toweri to allow us to distinguish different ESU's, so all fish belong to Atato1.

The left map shows the Río Tamuín basin from the Hydrographic Region Pánuco on a Mexico map. Within the Río Tamuín basin, the Bluetail Splitfin is restricted to the Río Verde subbasin (VER), shown on the right map:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Endangered/declining: „This species is known from the Media Luna and Los Anteojitos lakes, adjacent springs, their outlets near the city of Rioverde, and the Villa Juarez stream near the town of the same name (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005). Ataeniobius toweri associates closely with dense aquatic vegetation, and the recent loss of major macrophyte beds in Media Luna and Los Anteojitos have resulted in a substantial decline in the species abundance. At least two small nearby springs, Charco Azul and Los Peroles, maintain good populations. The Villa Juarez population persists but appears to be small.“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Ataeniobius toweri lives typically in quiet water with little or no current. It can be found along shallow margins of lagoons, marshes and ditches, but also in creeks where currents may be moderately strong. It prefers depths to 1m with the water very clear, but it may also be a bit murky. Typical vegetation associated with the Bluetail Splitfin are species of Nymphaea, Scirpus, Juncus and Eichhornia and green algae. The substrate is made of flocculent silt, mud, sand, gravel and rocks. A typical habitat is the Media Luna laggon. It includes an area with several warm springs and is located about 10km southwest of the city of Río Verde. Water from two caves forms a catchment area or reservoir that the natives call a lagoon. The clear water smells strongly sulfurous and the temperature ranges between 26° and 30°C.

On a survey in 2015, the GWG went to an El Aguaje called area near Villa Juarez. This is a swampy field with channels and ponds, built by the outflow of a small spring used for recreation. The current was moderate to swift and the water temperature about 26°C. The Bluetail Splitfin was found in the channels in small groups under the leaves of waterlilies and between reed stems. It avoided the swift flowing outflow from the spring as well as the shallow ponds. In 2017, another group surveyed a spring called Charco Azul south of Río Verde town, a middle sized clear spring, also used for recreation. The group concentrated on the clear outflow of the spring, where Ataeniobius toweri was found again hiding under leaves of waterlilies or between patches of submerse vegetation.

This species may be reproducing over a long period as individuals 11 and 14mm long were collected between November and March, and pregnant females were taken in May in a ciénega 10km south of Río Verde. Young fish occur in very shallow water (about 5cm) where sedges and grass are abundant. Growth and development progress slowly with sexual maturity occuring in six to seven months.

This species feeds mainly from algae and aufwuchs as suggested by its long coiled gut, but also small Crustacean. It usually nibbles on vertical stems of reed or waterlilies.

Meek described the colour in his orginal description as "dark brownish above, lighter below. Where the light and the dark colors meet the side more or less speckled; a narrow dark shade on middle of caudal peduncle." This is the colouration of preserved specimens. In life, the colour appears light grey (somewhat silver-grey) with two dark horizontal lines, one of them extends from the middle of the eye backwards to the caudal fin, the second one somewhat from the pectoral fin to the lower edge of the caudal fin. Some specimens show a varying number of vertical bars on the posterior half of the body, mainly on the caudal peduncle, extending from the end of the belly to the caudal fin. The number varies from 4 to 11. Breeding males show an azure caudal fin and whitish anal fin, some males become totally light blue.

At first appearance, males and females of the Bluetail Splitfin are not very easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Ataeniobius toweri have a slightly bigger Dorsal fin than females. A difference in colouration is almost not visible, except for the blue or bluish caudal fin in males, especially during the breeding time, when this blue can extend over the whole body and make the black lines almost invisible. Females always keep those two horizontal lines and a clear Caudal fin.

This is the only species of Splitfins, where fry does not develop Trophotaenia, therefore it was thought by Hubbs and Turner (1939) to be the most basal species of Goodeids. Later Turner stated (1940), that embryos clearly must absorb nutritents by other means. In 1983, Uyeno et al. suggested, that the Trophotaenia may have been lost secondarily, but only in 1989, Lombardi et al. showed that anal processes of near-term embryos, examined by light and electron microscopy, have prototypic trophotaenia. Large embryos and a large finfold, combined with the lack of competition with any other Goodeid species, may explain the loss of functional trophotaenia in newborn fish.

When Brian Kabbes visited La Media Luna in 1999, he pointed at the intensive use of the lagoon as a recreation area and at the excessive utilisation of water for agriculture. He also documented a partially destruction of the habitat according to that. Palacio-Nuñez et al. pointed at a similar situation in 2010. They complained about a bad tourism industry by destroying habitats, pollution and poor waste management. In the recent years, the upcoming diving tourism is leading to severe damages of submerse and riparian vegetation. Anteojitos and La Media Luna lakes are protected as reserves, but groundwater pumping in the region that may reduce spring inputs into the lakes and the introduction of non-native species both threaten the continued survival of Ataeniobius toweri (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005). Observations by Palacio-Nuñez et al. (2010) detected a strong correclation of Ataeniobius toweri with densely planted areas. Destroyed banks and competition through introduced Poeciliid species - they found a negative correlation in abundance of Striped Goodeids and Mollys (Poecilia mexicana) - are the main threat to this species.

Recent phylogenetic studies on Goodeids (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2012) revealed Ataeniobius toweri being closely related with the genus Skiffia and should therefore belong to the Girardinichthyini tribe, whereas Goodea atripinnis, that was thought to be closest relative to the Striped Splitfin, should belong to the Chapalichthyini. However, the position of both genera on the base of those tribes does not disagree with a close relationship between Ataeniobius and Goodea, it only suggests, that the common ancestor of them led to the splitting into two tribes.

Looking on the biotopes of Ataeniobius toweri, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with none to moderate current, structured with gravel, roots, branches, fallen leaves and submerse vegetation with vertical structures. Fry is usually not eaten, so it is easy to get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 100 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With roots and vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks, combined with maybe some bamboo or reed stems do best with this species. The current should be moderate to none, but due to the occurence in thermal springs and outflows, rich with oxygene, the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from algae and aufwuchs, additionally small insect larvae and Crustacean, so feeding with similar food, means algae overgrown structures, vegetables, water fleas and other small food from animalistic sources will be best for this fish. In aquarium, it feeds very well from flake food, granulate and tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. The species is acting a bit shy when kept in small numbers, but becomes active when kept in bigger groups.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 26°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 22°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. Though this fish lives in warmwater habitats, it does well over the winter time when kept cooler. It can be kept down to temperatures of 18°C without problems for months. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 23 or 24°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (28°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 18°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction might stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 18°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 22°C over the winter time to regulate reproduction.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Atato1-VER-MeLun

Population: Laguna Media Luna (Media Luna, La Media Luna)

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Tamuín

Subbasin: Río Verde

Locality: Laguna Media Luna, 7.5km SW of Rio Verde town

2. Atato1-VER-LAnte

Population: Los Anteojitos

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Tamuín

Subbasin: Río Verde

Locality: Los Anteojitos spring system, 5km S of Río Verde town

3. Atato1-VER-LCred

Population: Lago de Creda (aka Lago de Credo, Lago del Creda)

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Tamuín

Subbasin: Río Verde

Locality: (probably) in the marshy area S of the Media Luna lagoon - precise location point needs to be clarified, population eventually same as Atato1-VER-MeLun

4. Atato1-VER-RVer

Population: Río Verde

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Tamuín

Subbasin: Río Verde

Locality: precise location point unclear - needs to be clarified

5. Atato1-VER-ElAgu

Population: El Aguaje (aka Villa Juarez)

Hydrographic region: Pánuco

Basin: Río Tamuín

Subbasin: Río Verde

Locality: El Aguaje spring system, 2.5km S of Villa Juarez