- HOME

- WHO WE ARE

- NEWS AND DATES

- GOODEIDS

- PHYLOGENY

- ARTIFICIAL KEY

- GOODEID SPECIES

- BIOLOGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- CONSERVATION

- PROFUNDULIDS

- MEMBERS AREA

Allodontichthys tamazulae

English Name:

Peppered or Tuxpan Splitfin

Mexican Name:

Mexclapique (erronously: Mexcalpique) de Tamazula

Original Description:

TURNER, C. L. (1946): A contribution to the Taxonomy and Zoogeography of the Goodeid Fishes. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Zoology University Michigan No. 495: pp 1-15

Holotype:

Collection-number: University of Michigan Museum of Zoology, Cat. No. UMMZ-143022.

The Holotype is an adult female of 27mm standard length, collected by C. L. Turner on April the 3rd, 1939. Eight Paratypes, five males and three females (Cat. No. UMMZ-143023) were taken with the Holotype.

The left picture shows one of the oldest photos of Allodontichthys tamazulae, a male from the Río El Terrero, published in 1984 (E. Pürzl), the right picture the locality it was collected in 1971:

Terra typica:

The Holotype was collected in the Río Tamazula, the uppermost section of the Río Coahuayana before it changes the name into Río Tuxpan, just above the town of Tamazula de Giordano in Jalisco.

Etymology:

The species is named for the town of Tamazula de Giordano in the state of Jalisco, the type location of this fish. The name of the town again is from Nahuatl origin, the language of the Aztec people, with "tamazullan" meaning place or lagoon of toads.

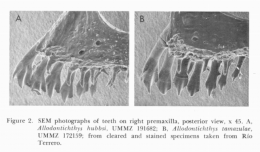

The genus Allodontichthys was erected by C. L. Hubbs and C. L. Turner in 1939 to distinguish this genus from the genus Zoogoneticus "chiefly on the basis of the form of the jaw teeth, which instead of being regularly conic (everywhere evenly round in cross section) are definitely compressed and shouldered within the slender conic tip and are keeled (rather weakly) at either edge of the anterior face." The generic name is derived from the ancient Greek language. The word ἄλλος (állos) means different, ὀδόντος (ódóntos) is the genitive of ὁδούς (ódoús), the tooth. The last part of the name, ἰχθύς (íchthús, íchthýs), is the Greek word for fish, so the name of the genus can be translated into "a fish with a different tooth".

Synonyms:

none

Distribution and ESU's:

The Tuxpan Splitfin is endemic to the Mexican federal state of Jalisco, historically widely distributed in the upper sections of the Río Coahuayana (Miller et al., 2005), named ríos Tamazula and Tuxpan (downstream to at least 45 river kilometres below the town of Tuxpan), and the upper Río El Tule drainage (ríos El Terrero and La Trampa), an affluent of the Río Naranjo, the name of the Río Coahuayana section following the Río Tuxpan. The historical extent of occurence included several affluents of the ríos Tamazula and Tuxpan, the ríos Contla, San Gregorio (San Jeronimo) and Atenquique, and the arroyos (creeks) Tecalitlán and Espanatica. Recent surveys (2019) revealed this species also from the Río Pihuamo, Río Ahuijullo drainage. Due to water pollution caused by sugarcane mills (e.g. Tamazula de Giordano), by sewage from the town of Tuxpan and by a huge paper mill in Atenquique can be inferred, that the main river nowadays is in some parts only scarcely populated, and the Río Tamazula past the sugarcane mill in Tamazula de Giordano almost uninhabitable (Lyons and Mercado-Silva, 2000). However, the species still inhabits the listed affluents and the Río Tamazula above the sugarcane mill and further downstreams in cleaner section of the river in good numbers. From the distribution in three distinct river systems, three subpopulations, the Río Tuxpan subpopulation (type subpopulation), the Rio Ahuijullo subpopulation and the Río El Tule subpopulation can be inferred. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of the first 3 letters of the genus, followed by the first 2 letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Allodontichthys tamazulae, only one ESU is accepted: Aldta1. This has to be seen with some caution, as the ríos El Tule and Ahuijullo subpopulations differ from the Río Tuxpan subpopulation at least in colouration and shape. Additionally, studies from S. A. Webb (2002), who compared two populations of Allodontichthys tamazulae, one Aquarium strain from the Río Tamazula, that most probably originated from the Río El Terrero instead (go for this to the chapter "Remarks"), and one wild caught one from Río Contla, revealed major genetic differences.

The left map shows the Río Coahuayana basin from the Hydrographic Region Armería-Coahuayana on a Mexico map. Within the Río Coahuayana basin, the Tamazula Splitfin occurs in three subbasins, shown on the right map: The Río Tuxpán subbasin (TUX) in the Río Coahuayana headwaters, the Río Coahuayana subbasin (COA) further downstreams, and the Río Ahuijullo subbasin (AHU), where it inhabits only northern tributaries:

Status :

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Vulnerable

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Vulnerable/stable: „Historically known from throughout the Upper Coahuayana River basin where it coexisted with A. hubbsi (Miller et al., 2005). Pollution from a sugar cane mill near the town of Tamazula has made a portion of the former range of the species in the lower Tamazula River uninhabitable since the 1970s (Lyons and Mercado-Silva, 2000). Our recent surveys have encountered A. tamazulae at ten locations, several of which had moderately large numbers of fish, and populations appear to be stable."

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): P - En Peligro de Extinción (in danger of extinction)

Habitat:

The habitats are generally small, rocky streams and riffles over substrates of sand, rocks and boulders. The vegetation is typically green algae, sometimes sparse or none, especially in large rivers where the species is scarce. The currents are slight or moderate to swift, the water is turbid or clear. It can be found in depths of 1m, but usually it prefers depths of 0.5m or less. Like all known Allodontichthys-species, the Peppered Splitfin is a bottom-dwelling and riffle-inhabitating species.

On a survey in 2016, a group of members of the GWG found this species together with Allodontichthys hubbsi and Ilyodon whitei close to the bridge at Contla in the Río or Arroyo Contla in very shallow (about 20cm deep) water in swift current. Both Allodontichthys species were easy to catch by lifting rocks, where the fish were hiding beneath, and putting a handnet over the place. The river had a width of about three to four meters in this dry season, the broad stony river bank sugested a width of about eight to ten meters in the rainy season, which could be confirmed on a second survey in November 2018. The first survey revealed good stocks of this species with nearly the same number of individuals as of the Whitepatch Splitfin. The group was able to find this fish additionally in the Río Tamazula at the east end of the town of Tamazula de Giordano, together with the same species of Goodeids and "Xenotoca" lyonsi in sligthly deeper water and swift current. On the second survey of the Río Contla in November 2018, it was a murky fast flowing river, wide up to 8 or 10m and deep to 120cm at some places. Only few Peppered Splitfins could be found this time, including fry (and two female "Xenotoca" lyonsi). A survey of the Río La Trampa in the same month revealed the species together with A. hubbsi above the town of San José de Tule near the aquaeduct, whereas in the town, only Allodontichthys tamazulae could be found. All Allodontichthys at all surveyed locations in November were in poor health condition probably due to a higher pressure through parasites. The health of fish was much better on a GWG survey only five months later in March and in June 2019 (dry season). The group found the Peppered Splitfin in the Río San Jeronimo and from its junction with the Tamazula river upstream throughout the whole Río Tamazula to the section between El Tulillo and the Presa El Charizo, additionally in the nameless creek N of la Garita, the Río El Terrero, the Río La Trampa and in the Río Pihuamo, Río Ahuijullo drainage. At most of the places the species occured in good numbers. A so far last survey of this drainage (June 2019) revealed Allodontichthys tamazulae also from the Río Tuxpan about 45 river kilometres below the town of Tuxpan, that`s more southern than it was known so far.

Biology:

Turner found no gravid females in April 1946, but Miller took individuals of 14–18mm SL between 24. February and 24. April. This suggests a reproduction during early winter. A survey of the GWG to the Río Coahuayana drainage in March and June 2019 found at almost all collection sites gravid females in different stages and fresh born fry.

GWG surveys in 2019 found this species in contrast to its congener Allodontichthys hubbsi, that was usually hiding under rocks and boulders, mainly within riparian vegetation and roots on the river bank, which might give a hint why it is possible for both species to co-exist (different habitat and/or food preference?). An underwater film taken in the Río La Trampa in March 2019 revealed Allodontichthys tamazulae in bigger numbers almost afloat in the current, while only few individuals of the Whitepatched Splitfin could be spotted hoovering beneath foliage and roots on the bottom of the river.

A survey of the GWG in 2016 found a decent number of hellgrammites, huge larvae of Dobsonflies (subfamily Corydalinae, family Corydalidae, order Megaloptera) covering in the mud of the Río Contla and hunting for fish, especially Ilyodon, but for Allodontichthys as well for sure.

Diet:

The conical and shouldered teeth and the short gut (2/3 to 3/4 of standard length) indicate carnivorous feeding habits. Turner found some large (5mm) insect larvae in the gut.

The left picture compares the upper jaw of Allodontichthys hubbsi (left) with tamazulae (right). It can be seen, that the jaw and teeth are oriented more horizontally in hubbsi, so eventually this species feeds in a different way than tamazulae (it may allow the species to go deeper between rocks and gravel to pick up the bait). The right picture shows a shrimp of the genus Macrobrachium. Juveniles of these common decapods would be a good food source for Allodontichthys-species.

Size:

The maximum known standard length is 73mm (Miller et al., 2005).

Colouration:

Turner described the colouration of preserved specimens in the following way: "In general the colouration of A. tamazulae is much lighter than of A. zonistius, and the entire portion above the lateral line is more lightly mottled with dark brown. About 12 heavy, dark, vertical bars extend in the females of A. zonistius from well above the lateral line to well below the lateral line, and a black comma-shaped patch is present just back of the pectoral fin. In A. tamazulae there are 18 to 22 very short dark bars along the lateral line. Only in the part anterior to the dorsal fin and behind the head is there any considerable extension of the bars below the lateral line. In this area 7 to 10 irregular bars extend downward upon the belly. The comma-shaped patch behind the pectoral fin is present in A. tamazulae, but is much lighter than it is in zonistius. Three light vertical bars occur upon the caudal fin in A. tamazulae. There are none in A. zonistius. All males are more heavily marked than the females, particularly in the vertical bars below the lateral line upon the belly."

Sexual Dimorphism:

At first appearance, males and females of the Peppered Splitfin are not as easy to distinguish from each other as sexes from other species of Goodeids, but easier than males and females from closer related species like Allodontichthys hubbsi or zonistius. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Allodontichthys tamazulae have a bigger Dorsal fin than females, and it is usually more intensively coloured, dark blotched or even almost black. A third character is the colour: males are brighter coloured, mainly blue or bluish on the back, with the upper part of the body clearly separated from the lower part by a series of black blotches forming an irregular line while females are duller coloured and mainly yellow.

Remarks:

In the 1980s, Miller & Uyeno postulated, that Allodontichthys hubbsi and tamazulae might be sister taxa, because they are distributed sympatrically and are of similar shape, but later phylogenetic results (Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I and mitochondrial control region, Webb, 2002) and morphological features (Rauchenberger, 1988, e.g. it differs from its congeners having only 3-3 versus 4-4 mandibular pores in the acustico-lateralis system, a longer base of the anal fin and the dorsal fin placed more anteriorly) heavily supported the position of Allodontichthys hubbsi at the basis of the genus as the most distinct representative. Latest phylogenetic studies (Cytochrome b gen, Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2011) however place the Whitepatch Splitfin again next to Allodontichthys tamazulae as its closest relative. Nevertheless some inconsistencies remain: How is it possible, that two species of one genus prefering similar habitats evolve in one river system, and how can it happen, that both persist next to each other? Here the emergence of different sex chromosmomes in Allodontichthys hubbsi could be the answer. But how can the morphological distinct features between hubbsi and its three congeners be explained? Maybe the relationship is not that narrow and the Whitepatch Splitfin is really the most basic species of Allodontichthys, but former hybridisation processes between Allodontichthys hubbsi and tamazulae may be pretending narrow relationship in the cytochrom b gen. Including several nuclear genes in phylogenetic studies migth bring an answer, but for the moment, the position of the species in the genus Allodontichthys is not clearly resolved.

The Whitepatched Splitfin occurs in most of the habitats sympatrically with Allodontichthys tamazulae. It is very likely, that both species are ecologically niched as surveys of the GWG found Allodontichthys tamazulae very often afloat or in dense root mesh of trees and riparian vegetation, where it regularly could be sampled on surveys in 2019, while Allodontichthys hubbsi was usually hiding under big rocks and boulders in the river course. Probably the species also prefer different food sources as can be inferred from the shape of the jaws.

S. A. Webb (2002) compared the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) and the mitochondrial control region sequences of all described Allodontichthys species, among them two populations of Allodontichthys tamazulae, one Aquarium strain from the Río Tamazula and one wild caught one from Río Contla, also from the Río Tamazula drainage. Surprisingly he found notably differences in the COI fragments of the two samples (13 substitutions, respectively a 2.1% sequence divergence), though both collection sites are only about 6km apart from each other. That is nearly as much as he found between polylepis and the clade zonistius plus tamazulae (2.4%). In the acknowledgements, he mentioned the aquarium population of the Peppered Splitfin going back to a founder collection of A. Radda. However, Radda didn't collect his fish in the Río Tamazula, but in the Río El Terrero, so it is quite sure, that Webb compared fish from the Río El Tule and the Río Tuxpan subpopulations.

J. Lyons and N. Mercado-Silva (2000) wrote, that in the field, the easiest possibility to distinguish A. tamazulae from thubbsi is by the colour of the back. While the Peppered Splitfin shows black or brown spots, the Whiteptach Splitfin doesn't have clear markings. Mary Rauchenberger (1988) described the dorsal body pigment of A. hubbsi as reduced in places, giving the fish a blotchy appearance. Additionally, she remarked pale fins in contrast to the other species.

First picture showing the backside of several Allodontichthys hubbsi and a single Allodontichthys tamazulae (left), second picture compares Allodontichthys tamazulae (above) and hubbsi (below) laterally:

Husbandry:

Looking on the biotopes of Allodontichthys tamazulae, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with gravel, rocks and boulders. It seems to be less aggressive than its congeners, nevertheless there is aggression between the adult fish, so the tank set up should prevent the fish from seeing each other all the time. Fry is eaten in most of the cases, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry may be neglected, so it makes sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 2 or 2.5cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 150 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With rocks well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate or swift, especially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle - sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, so feeding with similar food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources will be best for this predatory fish. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy and the species is not acting shy at all.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20 or 21°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (25°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 17°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 17°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Populations in holding:

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Aldta1-TUX-RTam

Population: Río Tamazula

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Coahuayana

Subbasin: Río Tuxpan

Locality: Río Tamazula, at NE end of Tamazula de Giordano

2. Aldta1-TUX-RCon

Population: Río Contla (aka Puente Contla, Arroyo Contla, Contla)

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Coahuayana

Subbasin: Río Tuxpan

Locality: Río Contla, at Contla

3. Aldta1-TUX-PCob

Population: Puente Cobianes (aka Río San Gregorio, Río Cobianes)

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Coahuayana

Subbasin: Río Tuxpan

Locality: Río San Gregorio, at the Puente Cobianes

4. Aldta1-COA-RTer

Population: Río El Terrero

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Coahuayana

Subbasin: Río Coahuayana

Locality: Río El Terrero, at 21. de Noviembre

5. Aldta1-AHU-RPih

Population: Río Pihuamo (aka Pihuamo)

Hydrographic region: Armería-Coahuayana

Basin: Río Coahuayana

Subbasin: Río Ahuijullo

Locality: Río Pihuamo, at Pihuamo