Skiffia multipunctata

PELLEGRIN, J. (1901): Poissons recueillis par M. L. Diguet dans lètat de Jalisco (Mexique). Bulletin du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, no 7: pp 204-207

Collection-number: Collection du Muséum National d'historíre naturelle de Paris, Cat. No. CMP-97/371-373.

The three specimens have total lengths of 62, 53 and 29mm, collected by L. Diguet, either 1899 or 1900. Pellegrin had both sexes at hand, watching Regans drawing of a male and a female dans below and the detailed description Pellegrin gave about the proliferation of the species. It was clear to him, that this species was a livebearing one when he found in one individual ten young fish fully developed and one of them already with the head out of the genital papilla ("L'espéce est vivipare, comme le prouve l'un des individus types qui contient une dizaine de petits complètement développés, don't l'un même, prêt à s'échapper, a déjà la tête engagée en dehors de l'orifice génital").

The left picture shows the first drawing of a male Skiffia multipunctata (Regan, 1907), the right one of a female:

The types were collected in lakes and ditches of Agua Azul in the vicinity of Guadalajara in Jalisco. When the fish were collected, Guadalajara had just reached a population size of 100.000 people (101.208 in 1900, Encyclopaedia Britannica from 1910). Today, the population is the second largest of Mexican cities with more than 5 million people in the metropolitan area. What had been vicinity in 1901 is now in the center of the city, like the Parque Agua Azul, meanwhile a recreation park without any fish living there, bearing the museum of Paleontology (Museo de Paleontología de Guadalajara).

The species' name is derived from the Latin with "multi" being the the plural of "multus", meaning many, and "punctatus" the adjective of "punctum", the spot, meaning marked with spots or spotted. The species epithet can therefore be translated with "marked with many spots". For Pellegrin, five to six rows of spots were remarkable enough to name the species after this colouration detail: "Sur les flancs et le pédicule caudal existent 5 ou 6 rangées de petites taches brunes au centre de chaque écaille". This means translated into English: On the flanks and the caudal peduncle were five to six rows of small brown dots in the centre of each scale.

The genus was erected by S. E. Meek in 1902 to honour Frederick James Volney Skiff, the 1st director of the Field Columbian Museum. Taking the latinized female version of his surname, Skiffia can be translated with "Skiffs one".

Xenendum multipunctatum Pellegrin, 1901

Goodea multipunctata Regan, 1907

Ollentodon multipunctatus Hubbs & Turner, 1937

The Spotted Skiffia is endemic to the Mexican federal states of Jalisco and Michoacán. It was historically known from the Lower Río Lerma drainage including several affluents like the Río Duero and from the Río Grande de Santiago/ Laguna Chapala drainage (including the Laguna Cajititlán) to about Guadalajara. It furthermore occured in the headwaters of the Río Guascuaro, Río Grande drainage (Río Balsas headwaters). Specimens from a historical collection in a river near Santa Cruz de las Flores, endorheic Laguna Atotonilco drainage, probably belonged to Skiffia francesae due to the hydrographic history of this basin (Zacoalco paleolake included parts of the upper Río Ameca drainage). Specimens from the Presa La Ciénaga (Presa Buenavista), upper Río Ameca drainage, should be Golden Skiffia as well due to the drainage. Pollution, habitat modifications, and introductions of non-native species have eliminated Skiffia multipunctata from Lake Chapala, the Santiago River basin, and parts of the lower Lerma River basin (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1998). The only area where the species remains is the Duero River drainage, but even there populations have disappeared from the lower portion of the drainage because of stream channelisation and water diversions for agriculture and probably also from Lake Camécuaro National Park because of the introduction of non-native largemouth black bass. Affiliated to three drainages, the Lower Río Lerma subpopulation (including the Río Duero), the Río Guascuaro and the Río Grande de Santiago/ Laguna Chapala subpopulation (type subpopulation) are distinguished. The type subpopulation is regarded Extinct, the Río Guascuaro subpopulation Data Deficient. The bold names are the ones officially used by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía; nevertheless, other ones might be more often in use or better known and therefore prefered.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of the first 3 letters of the genus, followed by the first 2 letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In Skiffia multipunctata, we are not able to distinguish any ESU's, so all fish belong to Skimu1.

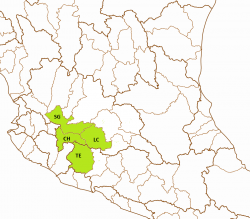

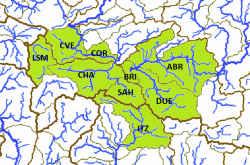

The left map shows the Lago de Chapala (CH), the Río Santiago-Guadalajara (SG) and the Río Lerma-Chapala (LC) basins from the Hydrographic Region Lerma-Santiago, and the Río Tepalcatepec (TE) basin from the Hydrographic Region Balsas on a Mexico map. The Spotted Skiffia is known from the ríos Duero (DUE), Briseñas-Laguna Chapala (BRI) and Angulo-Río Briseñas (ABR) subbasins from the Río Lerma-Chapala basin, historically also from the Laguna Chapala (CHA) subbasin and probably still from the Río Sahuayo (SAH) subbasins, Lago de Chapala basin. It occured or occurs in the vicinity of the Presa Tarécuato in the Río Itzícuaro (ITZ) subbasin, Río Tepalcatepec basin, and is historically known from the Río Corona-Río Verde (CVE) and the Laguna Chapala-Río Corona (COR) subbasins from the Río Santiago-Guadalajara basin. Collections near Santa Cruz de las Flores, Laguna de San Marcos (LSM) subbasin, Lago de Chapala basin seem to belong to this species and are therefore considered on this map there, while collections from the Río Cocula subbasin are probably erronously identified Skiffia francesae, so except for this last subbasins, the other ones are shown on the right map here:

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN): Endangered

Distribution and current conservation status of the Mexican Goodeidae (Lyons et al., 2019): Endangered/declining: „This species was found historically in Lake Chapala, the upper part of the Santiago River basin near the city of Guadalajara, including Lake Cajititlán, and the lower Lerma River basin, particularly the Duero River drainage (Domínguez-Domínguez et al., 2005). Pollution, habitat modifications, and introductions of non-native species have eliminated S. multipunctata from Lake Chapala, the Santiago River basin, and parts of the lower Lerma River basin (Lyons et al., 1998; Soto-Galera et al., 1998). The only area where the species remains is the Duero River drainage, but the species has disappeared from the lower portion of the drainage because of stream channelization and water diversions for agriculture. Only six or seven populations remain, with the largest found in the spring-fed La Luz and Orandino lakes. Populations in both lakes are threatened by habitat modifications for recreation and introductions of non-native fishes. Information on the larval ecology of S. multipunctata in captivity is provided by Escalera-Vázquez et al. (2004) and Kelley et al. (2005).“

NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010: Categoría de riesgo (Category of risk): A - Amenazada (threatened)

The habitats are small lakes, quiet river channels, spring-fed ponds and ditches over substrates of silt, mud, sand and rocks. Usually, the Splotched Splitfin prefers depths of less than 1m in clear to turbid water with currents none to moderate. The vegetation comprises green algae, duckweed, Typha and water hyacinths. In some habitats, there are plenty of roots from Taxodium, where this species is hiding and feeding from aufwuchs.

Surveys of the GWG to the La Luz spring, the type locality of Zoogoneticus purhepechus, in 2014, 2016 and 2018, the groups were able to observe this species in the wild. On underwater films, individuals were seen grazing algae and aufwuchs from rocks or swimming in small groups. One video captured a male imposing in front of a female while swimming around her like a butterfly. At all surveys the species was seen in quite good numbers.

Underwater-Videos:

Young have been captured from February to May, so the reproduction seems to be probably in spring. A survey of the GWG to the la Luz spring in March 2016 revealed gravid females ready to drop.

Like in all Skiffia-species, the gut is about 3 times the length of the fish. The teeth are mainly bifid in both rows, differing from Skiffia lermae where the inner band is composed of tiny conical or round-tipped teeth. This qualifies the species as a grazer. Like its closest relative, Skiffia francesae, this species is grazing aufwuchs and algae, sometimes from roots of Taxodium.

Skiffia multipunctata is very variable in colouration. The ground colour is in both sexes olive-brownish to brown-greyish with clear fins. Typically can be found tiny spots on the sides and the unpaired fins, sometimes in rows. Females usually keep this colouration, very rarely can be seen individuals with big dark blotches on the flanks that are much more typical for males. Male individuals may also be coloured yellow, yellowish or orange, sometimes only partially and displaying a bluish sheen on the forehead, especially during courtship. Male individuals may also express dark blotches on the flanks, extremly variable in number and size. While some males may show only one or two small ones, other ones might be covered almost totally in black. These blotches are not symmetrical, so in extrem cases, one fish might be unicoloured on one side and blotched on the other. There is no rule for size, number or distribution of blotches (see also the chapter "Remarks" for this phenomenon). By all means, male Skiffia multipunctata may belong to the most beautiful Goodeids we are able to find.

Males and females of the Splotched Skiffia are usually easy to distinguish. The safest characteristic is the Splitfin in males, means the for Goodeinae typical mating organ formed by a notch after the first seven shortened rays of the Anal fin. Additionally, male Skiffia multipunctata have a much bigger and notched Dorsal fin than females, giving it a serrated appearance on its anterior part. Males are typically more colourful and show yellow to yellowish flanks and unpaired fins. Blotches and and black spots on the flanks appear mostly on males, but not in all individuals (in nature, most of the males do not show black markings), and black blotches might also be shown by females in very rare cases.

James Langhammer crossbred Skiffia multipunctata and francesae in 1988. The hybrids had been fertile over generations, beautifully coloured with big black blotches on the sides and therefore called "Black Beauties". If some of these hybrids still exist in the United States is told differently and uncertain therefore.

In Skiffia multipunctata, we find the unique situation among Goodeids, that it had been placed twice in genera, that had been erected exclusively for Goodeid fish and lateron became synonyms. The first one is Xenendum that goes back to a mistake made by D. S. Jordan in 1880, when he erected the genus Goodea for fish with what he thought were tricuspid teeth, and 20 years later together with Snyder this genus for fish with biscuspid ones. When the original Jordan material of Goodea was studied again by T. H. Bean on behalf of Meek in 1902, and it was discovered, that the types of Goodea had only biscuspid teeth not trisuspid ones, the genus Xenendum correctly became a synonyme of Goodea. Skiffia multpunctata was originally described as Xenendum multipunctatun due to its similar dentition, but placed within Skiffia in the same paper of Meek, when he synonymized Xenendum with Goodea, so the synonym Goodea multipunctata could have been avoided. However, in 1907 Regan encompassed many genera and also placed Skiffia within Goodea. The etymology of the generic name can be derived from the ancient Greek with ξένος (xénos) meaning strange and ἔνδον (éndon) inner or internal. Herewith Xenendum can be translated with "internally strange", for sure an indication for the - at the beginning of the 20th century still unusual - presence of an ovarium filled with young fish ready to be born.

The second genus is Ollentodon, erected by Hubbs and Turner in Turners paper of 1937, where he pointed out, that among many other changes and the erection of genera this one is taken from the manuscript of the delayed monography about Goodeids, that finally was printed in 1939. In the opinion of the authors, Ollentodon differs from Skiffia "in having the teeth of the inner band mostly bifid, instead of conic or round-tipped;...". The generic name can be derived from the ancient Greek. The word óλλω (óllo) means "to lose" or "occasion a loss", and ἐντός (éntós) something like "within" or "among", and ὀδόντος (ódóntos), is the genitive of ὁδούς (ódoús), the tooth. The genus Ollentodon refers to the largely obsolent inner teeth and can be translated with "toothgap" or "diastema".

Moyaho et al. (2009) hypothized that female Skiffia multipunctata would prefer males with black blotches, but the results made clear, that females in contrary reject them: "However, in contrast to this hypothesis, females preferentially approached the males with less black colouration. Since orange colouration did not have a significant effect on female response, and there was no correlation between black and orange colours on the males in the study, females rejected males with more black colouration rather than preferring males with more orange or other visible colours. These findings indicate that sexual selection by female mate choice is not driving black or orange male body colouration in Skiffia multipunctata." Nevertheless, there must be a biological factor why blotched males do not disappear in the wild. An underwater film done by the GWG in 2014 showed that males with blotches also become almost invisible between rocks and algae, so there is no disadvantage for them that they would be caught easier by predators than not blotched males. However, more studies in this field would be welcomed as irregular and not symmetric blotching on this level (an individual may be black on one side and without blotching on the other) is almost unique among vertebrates in general. So far, there are only few examples known like Frogfish (Antennaridae, e.g. Antennarius maculatus), Cichlids of the genus Nimbochromis (e. g. Nimbochromis livingstonii) and the African Wild Dog (Lycaon pictus). In all these cases, the animals are predators and try to camouflage, the fish in a passive way pretending to be just structure of the reef (Antennarius spp.) or a rotting fish carcass to attract other fish (Nimbochromis spp.), the dog in the way to become invisible while sneaking up on prey.

Looking on the biotopes of Skiffia multipunctata, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with none to moderate current, structured with gravel, rocks, roots, branches, fallen leaves and submerse or/and river bank vegetation. Fry is usually not eaten, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide, so it is easy to get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 60 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With few rocks or roots and dense vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate, specially as the species is adapted to a high oxygene level (at least 8mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from algae and aufwuchs, but also from small invertebrates, so feeding with similar food like algae grown on feeding stones, blanched or boiled vegetables, water fleas and other small food from animalistic sources will be best for this predominantly herbivorous fish. In aquarium, it feeds also well from flake food, granulate and even tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. The species is not really shy, but likes to use hiding spots to observe the surrounding.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful. Otherwise, in combination with constant temperatures higher than 24°C, fish may get sick, lose resistance against diseases and age too fast. So for keeping the strain healthy and strong, give the fish a rest during winter time with temperatures lower than 20°C for 2 or 3 months so they stop producing fry. In spring, when the temperature slowly increases, they will start spawning at 20°C and won't stop until it gets colder again or when it gets too warm (24°C).

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by day exceeds 15°C and cold periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. During the warm summer, reproduction will stop and may occur again in fall. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 15°C by day and keep them cool for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature but try to stay below 20°C over the winter time.

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

1. Skimu1-DUE-Tan

Population: Tangancicuaro

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Duero

Locality: Cupátziro spring, Tangancicuaro de Arista

2. Skimu1-DUE-LCam

Population: Lago de Camécuaro (aka Camécuaro)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Duero

Locality: Lago de Camécuaro

3. Skimu1-DUE-RNue

Population: Rancho Nuevo

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Duero

Locality: channel near a new farmhouse about 5km NW of Jacona de Plancarte

4. Skimu1-DUE-LLuz

Population: La Luz (aka Presa de Verduzco, El Jachal del Rocha)

Hydrographic region: Lerma-Santiago

Basin: Río Lerma-Chapala

Subbasin: Río Duero

Locality: Presa de Verduzco, E of Jacona de Plancarte