- HOME

- WHO WE ARE

- NEWS AND DATES

- GOODEIDS

- PHYLOGENY

- ARTIFICIAL KEY

- GOODEID SPECIES

- BIOLOGY

- ENVIRONMENT

- CONSERVATION

- PROFUNDULIDS

- MEMBERS AREA

Crenichthys cf. nevadae

English Name:

Lockes Railroad Valley Springfish

Original Description:

undescribed species

Holotype:

undescribed species

Terra typica:

undescribed species

Etymology:

undescribed species

The genus was erected by Hubbs in 1932 with the generic name refering to the typical habitat of this genus, namely springs. It is derived from the ancient Greek with κρήνη (kréne or créne) meaning spring and ἰχθύς (íchthús, íchthýs), the Greek word for fish. The name of the genus simply means "Springfish".

Synonyms:

Crenichthys nevadae Hubbs, 1932

Distribution and ESU's:

The former Crenichthys nevadae was historically known from two isolated spring areas located in the range of the ancient Lake Railroad and being separated from each other by approximately 43km beeline. Following last phylogenetic results (Campbell and Piller, 2017), the southern population will have to be described as a separate species, while the northern one encompasses the "true" Crenichthys nevadae. We focus here only on this to be described species, that inhabits four springs near Lockes Ranch, namely Big, North, Hay Corral and Reynolds Springs. All of these springs are just a few hundred meters apart from each other.

ESU ist short for Evolutionarily Significant Unit. Each unit expresses an isolated population with different genetic characteristics within one species. ESU's can be defined by Molecular genetics, Morphology and/or Zoogeography and help in indicating different phylogenetic lineages within a species. The abbreviation for an ESU is composed of three letters of the genus, followed by the first two letters of the species name and an ongoing number in each species.

In the subfamily Empetrichyinae, no ESU's were in use so far. To align with the livebearing subfamily Goodeinae, the GWG wants to bring a system in use based on John Lyons' naming for this subfamily. In Crenichthys nevadae, we actually (until this species here is described) distinguish two ESU's based on genetics. Crene1 encompasses the two spring populations of Duckwater and the refuges populated with them out of its natural range, so the "true" C. nevadae, while Crene2 is in use for the populations of the four springs near Lockes Ranch, that belong to a separate species (Crenichthys cf. nevadae).

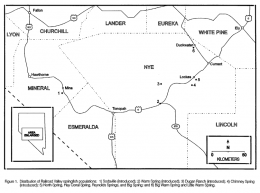

The left map shows the Central Nevada Desert Basins Accounting Unit (HUC 160600) of the Great Basin Region (HUC 16), the right map the Hot Creek-Railroad Valleys Cataloging Unit (HUC 16060012):

Status :

Habitat:

The Railroad Valley Springfish is found in warm spring pools, outflow streams, and adjacent marshes. Outflows tend to be shallow and less than 1m wide. The substrate of the head pools is typically sand, gravel or pebble with some decaying organic matter. Portions of some outflows contain dense mats of a nitrogen-fixing blue-green algae. Dense vegetation lines the pools and out-flows; salt grass is common in marshy areas. The springs and outflows at Lockes Ranch contain duck-weed and pondweed.

For more specific information, we took the habitat descriptions from the Railroad Valley Springfish Recovery Plan (1997), slightly modified: The four springs at Lockes are associated with a low hill of calcareous tufa that forms a bluff to the east and south. Their combined outflows produce approximately 6m³p.m. of water (Garside & Schilling, 1979). Big Spring, the largest in the Lockes spring complex, issues from the top of the tufahill. Its discharge was measured at 3.4m³p.m. in 1934, but between 1957 and 1967, the average discharge was 2.0m³p.m. (Garside & Schilling, 1979). Water temperature at the spring source was 32.5°C in 1934, but it has since increased to a range of 35 to 39°C. In 1980, the spring pool was 10m in diameter, 1.5m deep, and flowed into a narrow outflow with water depth decreasing downstream from 0.7 to 0.15m (Deacon et al., 1980). The outflow substrate was very soft mud with some sand and carbonate crusting. Current was negligible in the spring pool, but it increased down-gradient from 0.03 to 0.27ms. The outflow from Big Spring is diverted into two channels approximately 100m from the source. The northern outflow crosses under U.S. HW 6, runs parallel to the highway, crosses back under the highway, and then empties into a small livestock water pond. Both outflow channels are generally narrow with an average width of 1m, although the northern outflow is much broader due to continual trampling by cattle. Big Spring has been described as providing “borderline natural stressful conditions” for fish life (Deacon et al., 1980). The spring water is hard and alkaline, generally low in salt, very low in nitrates, and contains some sulfates. Dissolved oxygen is generally below 50% saturation. In 1980, the invertebrate community in Big Spring was low in species diversity, with generally only one representative from any of the eleven major groups present. Invertebrate abundance, however, was quite high, especially in algal mats. Sixty species of algae, belonging to five algal divisions, were identified. Blue green algae (Cyanophyta) represented the highest number of species and comprised the majority of the algal biomass in Big Spring. Diatoms were the most diverse algal group. Filamentous blue green algae was the main structural component of the aquatic vegetation community of Big Spring. All other algae grew within the masses of blue green algae. Six of the blue green algae species identified may be able to fix atmospheric nitrogen. If so, their presence is uniquely fundamental to the entire trophic structure of Big Spring (Deacon et al., 1980). North Spring discharges out of the northeastern side of the tufa hill without forming a pool at a rate that varied from 0.8m³p.m. in 1934 to 0.6m³p.m. in 1967 (Garside & Schilling, 1979). The spring’s outflow stream is diverted into two channels and eventually flows into a marsh. Water temperature at the source fluctuates between 34 and 36°C. Hay Corral Spring is located at the base of the tufa hill on the southeastern side. The spring’s main outflow stream is blocked by an earthen dam that creates a pool approximately 30m in diameter. The spring’s discharge was measured at 2.3m³p.m. in 1934 but dropped to 1.6m³p.m. in 1966 (Garside & Schilling, 1979). Recorded water temperature of the main spring has recently varied between 32 and 34°C. A smaller spring emerges below the dam and its outflow joins that of the main spring to flow into a marsh. The Reynolds Springs complex issues out of the southern base of the tufa hill. The two springs are approximately 10m apart, but their outflow streams combine almost immediately and eventually flow into a marsh. The combined discharge from the Reynolds Springs has varied from 1.1m³p.m. in 1934, 1.0 in 1967, and 1.3 in 1971 (Garside & Schilling, 1979). Water temperature has fluctuated between 35 and 37° C.

Biology:

Breeding in its sister species occurs year-round but ovary production documented from Big Warm Spring was greatest during the summer, declined in spring and fall, and was poorly developed in winter. When water temperatures were especially high, no larval fish were produced in any season. Reproduction seems to be severely restricted in water temperatures above 35°C. The ratio of males to females is even in the spring but the number of females almost doubles in the summer and fall.

Diet:

Primarily feeding herbivorous in spring, observations in summer show that Crenichthys cf. nevadae from Big Spring at Locke's Ranch is then carnivorous, preferring ostracods (Williams & Williams, 1989), but regarding the feeding habits of closely related inhabitants of thermal springs, it is probably an opportunistic omnivore, with animal food representing around 2/3 or more of its consumption during the summer, primarily consisting of gastropods. Plant consumption is mostly filamentous algae. While the intestine length is consistent with an omnivore with the mean ratio of digestive tract length to standard length around 1.30, Sigler & Sigler suggest that the high water temperatures of the Springfish habitat may demand the higher energy available with animal food.

Size:

The maximum known TL is 48mm (Williams, 1986)

Colouration:

The colouration of Crenichthys cf. nevadae is quite similar to that of the other species of the genus, especially to Crenichthys nevadae with which is shares a single lateral band of black blotches instead of two like in Crenichthys baileyi and its sister species from the Muddy River. The colour of the back is greenish brown to olive with the flanks partly in yellow or golden in adult males. The belly is white and a single lateral row of blotches is present, forming a dark band in adults and getting broader in older individuals. Fully grown up male specimens have a dark, sometimes almost black back, especially posteriorly, yellow to golden blotches on their flanks and a white to creme belly; females' colour is paler. The operculum is golden and fins milky to dusky bluish grey, confined by broad dark margins in males. Sometimes the unpair fins can become fully black or bluish black in males. The colouration is intensifying in excitement, a medial band on the back of the fish is shown, extending from the mouth to the dorsal fin origin and the golden colour gets striking.

Sexual Dimorphism:

The sexes differ mainly in shape, fins and colouration. Males are higher in body and appear stronger, anal and dorsal fins are longer and have a more sailfin shape while the these fins of females are shorter and the fins are rather shaped like a rhombus. Male unpair fins express a broad dark to black terminal band and are coloured more intensively while those of females stay mainly clear or are slightly coloured. Males have their lateral band broader than females but less distinct and the medial stripe in males is darker and more prominant, especially during courtship.

Remarks:

The following information is mostly taken from the Railroad Valley Springfish Recovery Plan (1997) and from the 5-year review from 2009, slightly modified and supplemented.

The Lockes Railroad Valley Springfish population estimates for Big Spring suggest a downwardtrend, from approximately 13,000 fish in July 1980, 4,200 fish inAugust 1989, and 2,700 fish in April 1993, to fewer than 100 in 1996. The North Spring population has fluctuated from an estimated 3,300 Springflsh in August 1989 to 860 in April 1993, and 3,500 in July 1994 to 930 in July 1996. The Hay Corral population estimate for August 1989 was 2,700 fish, expanded to 5,100 in April 1993, but dropped to 3,200 in August 1996. The Reynolds Springs population was estimated to contain 2,600 individuals in August 1989, and 4,500 in April 1993. Afterwards, Springfish abundance in Hay Corral Spring declined significantly due to habitat manipulation in 2001 when the spring outflow was diverted. Prior to the diversion, fish were found almost exclusively in the spring pool. After the outflow was diverted the majority of Springfish were distributed in the newly created ditch which provides less than optimal habitat conditions. North Spring, Big Spring and Reynolds Spring have had relatively stable habitat conditions since the Recovery Plan was published in 1997, and distributions of Springfish in these spring systems also appear to be relatively stable.Surveys have been conducted periodically, with different sampling methods, among the various sites since the Recovery Plan was published in 1997. A limited number of population estimates have been performed. Prior to listing, surveys at Lockes Ranch springs were completed infrequently. The populations ranged from nearly 10,000 in Big Spring to approximately 2,600 in Reynolds Spring. Annual or biannual surveys have occurred for the Springfish populations at Lockes Ranch since 1996; however, data are only reported from 1998 to current because of inconsistencies in the 1996-1997 survey data. Springfish abundance at Hay Corral Spring sharply declined between 2001 and 2002 when the private landowner modified the habitat. Since 2002, the population has increased in numbers with the catch per unit effort increasing ten fold. The catch per unit effort of fish at Reynolds Spring has decreased by more than 50 percent since 2001. There have been no habitat modifications at this site, so it is unknown why the population is declining. The population at Big Spring has fluctuated, but is relatively stable in size since 1999 with small changes in catch per unit effort. The catch per unit effort has ranged from a high of 4.3 fish caught per hour to a low of 1.68 fish per hour. The abundance of Springfish at North Spring declined sharply between 1998 and l999, and since 1999 the catch per unit effort has declined by over 50 percent. It is possible that the variability in the catch per unit effort at North Spring is due to changes in available habitat, the ability to set traps in dense vegetation, and/or the quality of the habitat (Hobbs, 2007).The private landowner, the Nevada Depratment of Wildlife (NDOP), and the Service began negotiations for purchase of the property under a Service Recovery Land Acquisition Grant in 2002. In 2005, the Lockes Ranch complex of historical habitat was purchased by the State of Nevada. Shortly after the purchase of Lockes Ranch, a habitat restoration and management plan for the four springs and their associated outflows was developed. This plan was completed in April 2006, and restoration activities were completed in fall 2008. NDOW restored much of the historical outflows and, most importantly, restored them to the historical widths and depths that facilitate transport of thermal water which will improve habitat conditions for the Springfish. Restoration activities included creation of a new sinuous channel, improvement of existing channels, dewatering of a man made irrigation ditch that was previously used for stock watering, and removal of nonnative vegetation surrounding the four Spring systems.

In 1977, a population of Railroad Valley Springfish was discovered in an unnamed warm spring on private property at the Dugan Ranch in Hot Creek Canyon, Nye County, Nevada, 65km W of Lockes Ranch, presumably the result of an unauthorized transplant (Allan, 1983). In 1984, 1,775 Springfish were captured from the Dugan Ranch spring complex at a rate of 27 fish per trap hour (Deacon, 1984). Springfish were abundant in the Dugan Ranch spring during the summers of 1990 and 1992 (Sjoberg, 1990; Heinrich, 1992). The thermal spring at the Dugan Ranch had a measured discharge of 1.4m³p.m. at 34°CC in 1965 and 1.8m³p.m. at 36°C in 1967 (Garside & Schilling, 1979). No formal surveys have been conducted at Hot Creek Canyon; however, sampling in 1984 and from 1996 to 2001 indicated that Springfish were present (NDOW, 2001). Visual surveys in 2007 documented that the population was still present (Hobbs, 2007). Two other sites west of the Old Dugan Ranch were also visually surveyed in 2007 and had populations despite the small size of the springs (Hobbs, 2007). According to visual surveys conducted by NDOW in 2007, conditions at the Old Dugan Ranch in Hot Creek Canyon have changed since the last visit in 2001. American bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) and Australian redclaw crayfish (Cherax quadricarinatus) have been introduced where the fish occur, which has likely had a negative impact on them. However, the habitat is in sufficient condition to support a small population of less than 1,000 springfish (Hobbs, 2007). Two other sites were also confirmed to contain springfish in Hot Creek Canyon by NDOW in 2007. One site, just a few miles west of the Old Dugan Ranch, was previously documented by NDOW in the mid 1990’s; however, in 2007 the population was widespread and visually estimated to be at least in the hundreds with all age classes present (Hobbs, 2007). Another site, also within a few miles west of the Old Dugan Ranch, was previously unknown and has a small population (less than 300) of Springfish comprised of multiple age classes. The latter two sites do not contain bullfrogs or crayfish. A survey of the Nevada Department of Wildlife to the Hot Creek area in summer 2021 is on plan (Guadalupe, pers. com., 2021).

In 1978, Bureau of Land Management and Nevada Department of Wildlife personnel released Lockes Railroad Valley Springfish from Big Spring into three ponds created at Chimney Spring, 10km south of Lockes (Williams, 1986). The Chimney Spring population has had two major setbacks since being established. The fish were abundant in all three ponds during January 1981. During June 1981, however, spring discharge decreased to the extent that all fish were extirpated from the Chimney Spring system by early August 1981. Spring discharge increased in late August 1981 and spring flow and water temperature regimes in each pond had been restored by November 1981 (Williams, 1986). Springfish from Big Spring were again released into Chimney Spring in May 1982, and the population was estimated to contain 1,900 fish in May 1985. In May 1988, cattle entered the Chimney Spring livestock exclosure and severely trampled the berms creating the three ponds. By June 1988, no fish remained in the ponds, but a few were observed downstream (Williams & Williams, 1989). Following repair of the ponds, these remaining fish recolonized the ponds during 1989, and the resultant population was estimated to contain 5,800 individuals in 1994. Chimney Spring issues from the top of a travertine hill approximately 800m in diameter and 10m high. The spring discharge rate was 0.4m³p.m. in 1934 and 1965 (Garside & Schilling, 1979). The water from this spring is the hottest in Railroad Valley, ranging from 63 to 66°C. The outflow has been channelized and flows into a succession of three ponds before continuing down the side of the hill and seeping into the ground. The Chimney Spring system consists of a natural springhead and a series of three artificial ponds on the outflow. The outflow is subject to ongoing natural modification caused by deposition of minerals contained in the spring water. Mineral deposits tend to gradually divert the water flow away from the ponds containing fish, and dense stands of emergent aquatic vegetation make the ponds smaller and shallower over time. The ponds were excavated in 1997 as part of a habitat improvement plan. Prior to excavation, Springfish were found in two out of three ponds; July 1998 surveys documented them in all three ponds (Stein, 1997). The population at Chimney Spring was present in all three ponds (Morrel et al., 2007) and numbers were stable until 2007, when Chimney Hot Spring and the ponds went dry and no Springfish survived. The Chimney Spring population went definitely extinct (Guadalupe, pers. com., 2021)

Terrace Hot Spring is located approximately 800m from Chimney Hot Spring where it is believed that a flash flood event transported Springfish from Chimney Hot Spring to Terrace Hot Spring sometime between 1995 and 1998. The population there was discovered in 1998 (Stein, 1999). Terrace Hot Spring is visited approximately every other year where visual observations have verified that this population’s distribution remains stable (Morrel et al., 2007). The spring is not physically surveyed (trapped) because of the high water temperatures in the spring pool and along the outflow. Trapping Springfish under those conditions could cause heat stress and eventual death. In 1998, the population at Terrace Hot Spring was estimated to be in the thousands (Stein, 1998). Annual visual surveys conducted since 1998 have documented approximately 500 fish along the outflow. Fish were still present in 2017, but springs are receiving some habitat alteration by people who illegally use them as soaking pools. Terrace Hot Springs has been highly illegally modified as of recent (Guadalupe, pers. com., 2021).

In 1992, The Nevada Department of Wildlife reported another introduced population of Lockes Railroad Valley Springfish on private property at Warm Spring near the junction of U.S. HW 6 and Nevada Highway 375, Nye County, Nevada. Warm Spring, also referred to as Nanny Goat Spring, discharged 2.6m³p.m. of water in October 1965, and it has varied between 60 and 63°C. Warm Spring is on private land and is used for cattle watering. The fish population at Warm Spring was doing well until a backhoe was used to clean the channel, which severely altered the outflow and eliminated much of the habitat (Heinrich, 1993). By the late 1980’s, the Warm Spring refugium population of Springfish was extirpated and none were found at this site during a visual survey conducted in the autumn of 1994. The Warm Spring population defintely went extinct (Guadalupe, pers. com., 2021).

The left picture shows the natural habitats and known introductions of Crenichthys nevadae and its sister species with numbers 5 (native range) and 2,3 and 4 (introduction sites) belonging to Crenichthys cf. nevadae, the right picture a more detailed map of Lockes Ranch:

Species of the subfamily Empetrichthyinae are oviparous fishes and share the lack of pelvic fins, while the subfamily Goodeinae is livebearing. Lynne Parenti (1981) finally proposed this subfamily as sister group to the Goodeinae and encompassed both in the family Goodeidae. Meanwhile the monophyly of the family Goodeidae and the narrow relationship between both subfamilies has been supported through several studies since the 1980's and is not doubted any longer.

In 2017, D. Cooper Campbell and Kyle R. Piller pubished a phylogenetic study of the Empetrichthyinae. Concerning Crenichthys nevadae, individuals from seven localities were included, namely the four springs on Lockes Ranch, Hot Terracy Spring, and from the Duckwater Reservation School Spring and Little Warm Spring. The studies were separatly done on the mitochondrial gene Cytochrome b and three nucleotide sequences, namely S7 intron-1, S8 intron-4, and P0 intron-1. Concerning cytb, the authors found two clades corresponding with the two distribution areas and genetic distances between 1.6 and 1.8%. Concerning the three introns, a clade formed by the southern ones from Lockes Ranch and Hot Terrace Spring was recognized, and Haplotype network analysis recognized two separate clades as well. Phylogeny from species tree analysis based on cytb hypothesis following Bayesian statistics supports a model of two species. Taking in consideration genetic distances in the cytb gene that separate species in the Goodeinae and the result of the tree analyis, we follow a conservative approach here and recognize two species: Crenichthys nevadae from the type locality (Big Warm Spring, Duckwater) and Crenichthys cf. nevadae from the southern habitats next to Lockes Ranch.

Husbandry:

Looking on the biotopes of Crenichthys cf. nevadae, they suggest the species may prefer a habitat with moderate to swift current, structured with gravel, rocks, roots, branches, fallen leaves and river bank vegetation. Fry is rarely eaten, but it may depend on the quantity and quality of food and on the number of places to hide. When several different stages of juveniles occur, fry will be neglected, so it makes eventually sense to add separate brought up fry to the group with a size of 1.5 or 2cm to provide these stages and get a flock breeding colony.

The recommended tank size is at least 100 liters, bigger tanks with a generous base and little height (25cm are enough) are better for sure. With rocks and vegetation in the corners and backside of the tank well structured tanks combined with some roots and/or wood seem to do best with this species. The current should be moderate or swift, but the species can deal wih low oxygen values (down to 3mg/l).

In the wild, the species feeds mainly from small or middle-sized invertebrates like bloodworms or insect larvae, gammarids, ostracods, but also algae, aufwuchs, detritus and other organic matters, so feeding with similar food, water fleas, Mysids and other food from animalistic sources as well as stones and pebbles covered with green algae will be best for this omnivorous fish. In aquarium, it feeds very well from flake food, granulate and tablets, additionally given Nauplia of Brine Shrimps are eaten greedy. Additionally, as aufwuchs and green algae are taken in the natural habitat, providing some kind of vegetables like boiled peas is a good food supplement. The species is not shy.

Concerning water quality, this species is in need of bigger water changes (60-80% every week) like most of the Goodeids, especially river and spring inhabiting species, so an automatic water changing system can be helpful, but in contrast to most of the Goodeid species from Mexico, it needs to be temperated and the oxygen level could be low. This species does best at temperatures between 25 and 29°C though it is able to withstand lower temperatures down to even 12°C for a short period.

This species is doing very well when is kept in the open from spring to fall, starting when the water temperature by night does no more deceed 18°C and colder periods are no longer expected. Bring them out in the early afternoon, the time of the day with the highest water temperature. Bring the fish in before the water temperature deceeds 18°C by night and keep them at this temperature for the first days, then slowly raise the temperature to the convenient range of this species over the winter time.

Populations in holding:

Here each species are assigned populations of fish in husbandry and in brackets aliases of these locations to assist in identifying own stocks. Each population is assigned a unique Population-ID, composed by the ESU, the subbasin where this population is occurring (three capital letters) and a unique location identifier.

Populations in holding:

none